Cathar Eclipse

The story of the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars

The desire for worldly power and the pursuit of religion are incompatible bedfellows, but throughout history they have been difficult to separate. Even to the present, day leaders of every race continue to pass off their personal ambition as the word of God. It is understandable, for by so doing, territorial aggression can be justified and elevated to the status of Holy War, forays of theft and murder can be dignified as crusades and the atrocities that inevitably result, shrugged off as acts of divine vengeance.

This tendency was abundantly illustrated in the 12th and 13th centuries when religious fervour suffused every aspect of society. The Roman Catholic Church had successfully monopolised Christianity and would tolerate no rivals. God was glorified through the display of its power, richness and magnificence. Awe-inspiring cathedrals were built and their clerics decked out in splendid robes to conduct mystic ceremonies in a language few understood. However, many devout believers remembered the simplicity of Jesus and saw how stark was the contrast between His teachings and the arrogance displayed by the Church. Christian principles had disappeared into a quagmire of power play and this gave rise to a series of breakaway movements seeking to worship independently. However, the Church would have none of it. Anyone questioning its practices was declared a heretic and heresy was treason against God. The perpetrators were put down with self-righteous cruelty.

The various heresies arose independently, but they all shared one thing in common; a revulsion against the conduct of the orthodox church itself. Nevertheless the Church was supremely confident that it held the keys to salvation and it intended to hold on to them by fair means or foul.

The castle of Puivert

One of the many small chateaux of southern France that became a haven for musicians and poets during the time of the troubadours. It was taken by assault by Simon de Montfort in 1210.

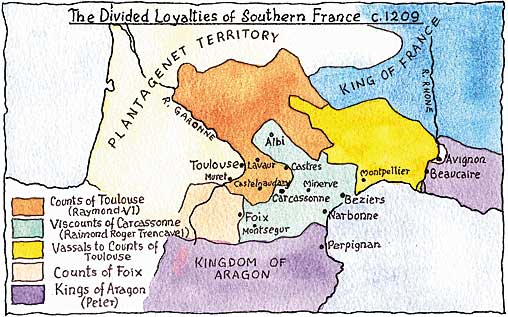

The tendency towards independent thinking was particularly marked in Languedoc; that great sweep of southern France that extends eastwards from the Pyrenees to the Rhone valley where the Occitan dialect; the langue d’Oc, was spoken. It was an independent region by nature. At the turn of the 13th century its political affiliations were so tenuous and fragmented that its dukes were kings in all but name. Only the Church exercised a measure of overall control. The most powerful ruler in Languedoc was the Count of Toulouse. A rival dynasty was the house of Trencavel. Its viscounts ruled the regions around Carcassonne and Béziers. Nominally they were vassals to the Counts of Toulouse, but in reality they were more like rivals. The Trencavels were also allied by marriage to the King of Aragon and had openly declared their allegiance to him.

Despite all the divided loyalties and continual friction, the provinces of Languedoc were rich and prosperous, exciting the envy of other poorer and more troubled regions of France.

Its nobles could afford to relax whilst their ladies indulged in leisure activities and became the arbiters of taste and fashion. The many small castles opened their doors to all manner of roving troubadours who could fill their halls with music and poetry. For a brief moment in time Languedoc was a fortunate land; famous throughout Europe for its poetry and song. It was in this tolerant environment that independent religious ideas were able to take root and flourish.

Pope Innocent III

From a 13C. fresco in the church of Subiaco in Italy.

The troubadours sang of love and war but they also mocked the immorality and licentiousness of the local prelates.

Pope Innocent III too was disturbed by the behaviour of his priests. He was a brilliant pope, ruthless, totalitarian and implacably devoted to increasing the power of the Catholic Church.

He was ready to order the mass extermination of any group Christian or otherwise, that stood in his way and he could see that the widespread corruption of his clerics was corroding the influence of the Church. Of the Archbishop of Narbonne he wrote:

“…He knows no other god but money and has a purse where his heart should be. His monks and canons take mistresses and live by usury… Throughout the region the prelates are the laughing stock of the laity.”

With the Orthodox Church in such disarray it is not surprising that ordinary people were attracted to a creed that put Christian humility and love before the arrogance of power.